Asthma in pregnancy

Prescribing In Pregnancy

Diabetes in pregnancy

Asthma in pregnancy

Table of content

1. Introduction

2. Clinical features

3. Diagnosis

4. Indication for referral

5. Pre-pregnancy care

6. Effects of pregnancy on asthma

7. Effects of asthma on pregnancy

8. Management

9. Common drugs used in pregnancy that have effect on asthma

10. British thoracic society step up guidance on asthma medications

11. Management of acute asthma in pregnancy/labour

12. Reference

Introduction

- The majority of women with asthma have normal pregnancies and the risk of complications is small in those with well-controlled asthma.

- During pregnancy asthma control often changes, presumably related to hormonal influences, though it is unpredictable. Many women’s asthma control improves in pregnancy, whilst others get significantly worse. In general one third get better, one third worsens and one third stay the same during pregnancy. Repeat pregnancies do not follow the pattern of previous pregnancies.

- Symptoms of breathlessness in those with severe or poorly controlled asthma tend to worsen during pregnancy, presumably due to the added physiological burden due to reduced lung volumes and increased metabolic demands in those already compromised. Studies suggest that 11–18% of pregnant women with asthma will have at least one emergency department visit for acute asthma and of these 62% will require hospitalisation. Exacerbations are more common between 24 and 36 weeks

Clinical features

Symptoms

- Breathlessness, cough, wheezy breathing, chest tightness, nocturnal waking due to cough

- Triggering Factors: Pollen, animal dander, dust, cough, exercise, cold, emotion, upper respiratory infections, medications (aspirin, beta blockers)

Signs:

- Raised respiratory rate, wheeze, use of accessory muscles, tachycardia

Diagnosis

- History – Signs and symptoms, history of atopy, (personal or family)

- Measurement of FEV1 (Forced expiratory volume) and FVC (Forced vital capacity) by spirometry. Ideally this will be supplemented by evidence of reversibility (12% improvement to a bronchodilator or even an inhaled steroid or oral steroids.

- A more than 20% diurnal variation in PEFR (Peak expiratory flow rate) for 3 or more days per week during a 2-week diary is a diagnostic option

- New guidance recommends the use of a raised FeNO (fractional exhaled nitric oxide) as a marker of airway inflammation

- In more complex cases, assessment by a specialist team might be needed.

Indications for referral

The indications for uncontrolled asthma symptoms and the need for referral to a joint Multidisciplinary Obstetric Respiratory clinic within a tertiary setting include:

- Daytime symptoms

- Night time awakening due to asthma, defined as waking with asthma 1 or more times per week

- Need for rescue medication – patients requiring add on therapy beyond Inhaled short-acting β agonist and inhaled steroids and patients with persistent poor control

- Asthma attacks / exacerbations requiring frequent oral corticosteroids or hospitalisation

- A history of life-threatening attacks

- Limitation of daily activity

- FEV1< 80% of expected

Pre-pregnancy care

All professionals providing care for women of childbearing age including general practitioners and obstetricians should be educated regarding the facts:

- It should be explained to women that there is some evidence that the course of asthma is similar in successive pregnancies.

- Women with asthma should be specifically advised not to stop or decrease their asthma medication when they find they are pregnant including both inhaled and oral steroids as the benefits of the medication outweigh the risks.

- There are as yet no clinical data on the use of omalizumab for moderate-severe allergic asthma in pregnancy. Some data from the EXPECT study suggests that if women are already using it when they get pregnant, they should continue to do so following a discussion with the patient but that it shouldn’t be started in pregnancy unless there are no alternatives.

- Control of asthma should be optimised before conception.

- The only treatment commonly used by asthmatic patients, known to be harmful to pregnancy is the antibiotic, doxycycline. Azithromycin should also be discontinued in pregnancy.

Effects of pregnancy on asthma

- Asthma may improve, worsen or remain unchanged in pregnancy

- Women with mild asthma are unlikely to experience problems relating to their asthma or its treatment in pregnancy.

- An asthma attack during labour is extremely unlikely due to increased production of endogenous steroids

- The most common cause of deterioration in disease control in pregnancy is caused by reduction or even complete cessation of medication due to fears about its safety and itself is the biggest risk to the baby.

Effects of asthma on pregnancy

- In the majority of women there are no adverse effects

- Severe (when inadequately treated) and poorly controlled asthma may adversely affect the fetus

- There is some association between asthma and following conditions: pregnancy induced hypertension & pre-eclampsia, preterm births and preterm labour, fetal growth restriction, neonatal morbidity (transient tachypnoea of new born, admission to neonatal unit, seizures). Most of these are entirely caused by poor asthma control and not by its effective treatment.

Management

Antenatal

- Women should be encouraged to stop smoking. Reference to smoking cessation programs are helpful where indicated

- Avoid known trigger factors

- Reassurance regarding the asthma medications to improve treatment adherence for the duration of pregnancy

- Personalised self-management plans should be encouraged

- Measurement of FeNO during pregnancy has been associated with better outcomes as it directs appropriate and adequate anti-inflammatory control.

- Counselled about indications for an increase in inhaled steroid dosage and if appropriate given an emergency rescue supply of oral steroids

- Serial growth scans should be performed in women with severe asthma

- Early referral to anaesthetist should occur if asthma is severe or poorly controlled

Intrapartum

- Asthma attacks are exceedingly rare in labour due to endogenous steroids

- Women should not discontinue their inhalers during labour as there is no evidence to suggest that beta 2 agonists inhalers will impair uterine contractions. Whilst the woman is on inhaled salbutamol there is very minimal systemic absorption to warrant monitoring blood glucose levels in the baby after birth.

- Women receiving oral steroids (7.5mg/day for more than 2 weeks) should receive parenteral hydrocortisone 100mg 8 to 12 hourly to cover the stress of labour.

- Oxygen should be delivered if saturation falls below 94–98% in order to prevent maternal and fetal hypoxia. If this occurs, help should be sought from respiratory or preferably asthma specialists.

- Prostaglandin E2 are safe to use, when needed.

- Use of Prostaglandin F2α to treat life threatening postpartum haemorrhage may be unavoidable, but it can cause bronchospasm and should be used with caution (ICU and respiratory teams should be involved when they are being used).

- Epidural anaesthesia is recommended as the best option for women opting for pain relief.

- Continuous fetal monitoring should be performed when asthma is uncontrolled or severe.

- Ergometrine may aggravate bronchospasm especially when general anaesthesia is used.

- Regional rather than general anaesthesia is preferable because of the decreased risk of chest infection and post-operative atelectasis.

- Caesarean section is reserved largely for obstetric indications. In certain situations where the asthma is severe a decision to perform caesarean may be made in close conjunction with the respiratory physician, to ensure a safe pre-term delivery.

- When interpreting arterial blood gases in pregnancy it should be remembered that the progesterone-driven increase in minute ventilation may lead to relative hypocapnia and a respiratory alkalosis, and higher PaO2, but oxygen saturations are unaltered

Postnatal

- Most of the medications including oral steroids are safe in breast feeding mothers, however if the woman is restarted on Azithromycin breastfeeding should not be encouraged.

- The risk of atopic disease developing in the child of a woman with asthma is about 1 in 10, or 1 in 3 if both parents are atopic.

- There is some evidence that breast feeding may reduce the risk of asthma in baby

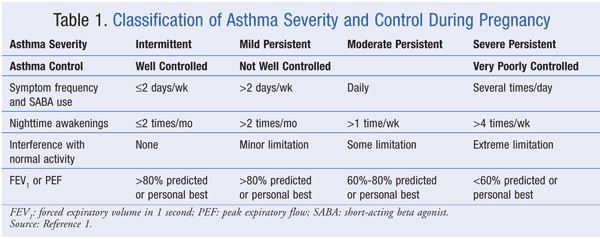

Classification of severity

Common drugs used in pregnancy that have an effect on asthma

- Prostaglandin E2: Propess, Prostin- is a bronchodilator and is safe.

- Prostaglandin F2α: Carboprost – should be used with caution as it may cause bronchospasm.

- Entonox: Safe to use

- Epidural analgesia/Spinal anaesthetic: Safe to use

- General anaesthetic: Increased risk of chest infection and associated atelectasis

- Opiates: Should be avoided in acute exacerbation of asthma.

- Ergometrine: Can cause bronchospasm, particularly in association with general anaesthesia. Syntometrine (oxytocin/ergometrine) is less problematic

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and Aspirin: Avoid if known sensitivity to these drugs

British thoracic society step up guidance on asthma medications

Advice should be given regarding

- In general medicines used to treat asthma are safe in pregnancy

- The risk of harm to the fetus from severe or chronically undertreated asthma outweighs any small risk from the medications used to control asthma

- Use all the drugs mentioned below as normal in pregnancy including oral steroid tablets

- Perform blood levels of theophylline in pregnant women with acute severe asthma and in those critically dependent on therapeutic theophylline levels

- No adverse perinatal outcome and exposure to sodium cromoglicate and nedocromil sodium has been documented.

Step 1 – Mild intermittent asthma

- Inhaled short-acting β agonist as required

Step 2 – Regular preventer therapy

- Add inhaled corticosteroid 200-800 micrograms/day 400 micrograms is an appropriate starting dose for many patients

Step 3 – Initial add-on therapy

- Add inhaled long-acting β agonist (LABA)

- Assess control of asthma:

- Good response to LABA – continue LABA

- Benefit from LABA but control still inadequate – continue LABA and increase inhaled corticosteroid dose to 800 micrograms/day

- No response to LABA – stops LABA and increase inhaled corticosteroid to 800 micrograms / day. If control still inadequate, start other therapies as leukotriene receptor antagonist (LRA) or SR (sustained release) theophylline

Step 4 – Persistent poor control

- Increasing inhaled corticosteroid up to 2,000 micrograms / day

- Addition of fourth drug e.g. LRA, SR theophylline, β 2 agonist tablet

Step 5 – Continuous or frequent use of oral steroids

- Use daily steroid tablet in lowest dose providing adequate control

- Maintain high dose inhaled corticosteroid at 2,000 micrograms/day

Management of acute asthma in pregnancy / labour

Acute severe asthma in pregnancy is an emergency and should be treated vigorously in hospital

A diagnosis of acute severe asthma is made when:

- PEF 33-50% best or predicted

- Respiratory rate ≥25/min

- Heart rate ≥110/min

- Inability to complete sentences in one breath

Life threatening asthma: In a patient with severe asthma any one of:

- PEF <33% best or predicted

- SpO2 <92%

- PaO2 <8 kPa

- Normal or raised PaCO2 (4.6-6.0 kPa)

- Silent chest, cyanosis, poor respiratory effort

- Arrhythmia, exhaustion, hypotension, altered consciousness

Near fatal asthma

- Raised PaCO2 and/or requiring mechanical ventilation with raised inflation pressures

Treatment of acute and severe asthma

Severe asthma in pregnancy is a medical emergency and should be vigorously treated in hospital in conjunction with the respiratory physicians.

- Treatment of severe asthma is not different from the non-pregnant patients

- Treatment should include the following;

- High flow oxygen to maintain saturation of 94- 98%

- β2 agonists administered via nebulizer which may need to be given repeatedly

- Nebulised ipratropium bromide should be added for severe or poorly responding asthma

- Corticosteroids ( IV hydrocortisone 100mg) and /or oral(40-50mg prednisolone for at least 5 days)

- Chest radiograph should be performed if there is any clinical suspicion of pneumonia or pneumothorax or if the woman fails to improve

- Management of life threatening or acute severe asthma that fails to respond should involve consultation with the critical care team and consideration should be given IV β2 agonists, IV magnesium sulphate and IV aminophylline

References

- British guideline on the management of asthma October 2016

- Handbook of Obstetric Medicine: Catherine Nelson-Piercy

- Asthma in pregnancy: The Obstetrician and Gynaecologist Journal 2013; 15:241-5

- Namazy J et al: The Xolair Pregnancy Registry (EXPECT): the safety of omalizumab use during pregnancy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Feb;135(2):407-12.